Effect of Moisture on Building Systems!

There is always some moisture in the air around us. An indoor relative humidity of about 50% is usually considered a healthy level because it is comfortable for humans and because many molds and mites are unlikely to thrive in that environment.

When is Moisture a Problem?

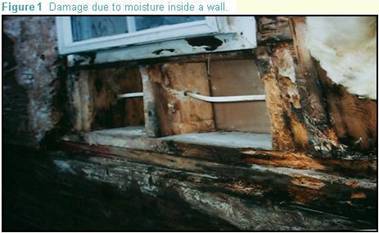

Even though you need some moisture in the air you breathe, too much moisture in your home can cause problems. When moist air touches a cold surface, some of the moisture may leave the air, condense and become liquid. If this happens on a cold pane of window glass, you will see the water run down and collect on the window sill, where it may ruin the paint or rot the wood trim. The water may even freeze, producing frost on the inside surface of the window. If moisture condenses inside a wall, or in your attic, you will not be able to see the water, but it can cause a number of problems. For example, mold and mildew grow in moist areas, causing allergic reactions and potentially damaging the building. Structural wood may rot and drywall can swell (see Figure 1). If moisture gets into your insulation, the insulation will not work as well as it should, and your heating and cooling bills will increase.

How Does Moisture Come into Your Home, and How Does it Move Around Inside the Building?

The most obvious way that moisture enters your home is through rain, either falling on a leaky roof, wind-driven against a poorly-sealed wall, or collecting against (and eventually leaking through) the walls of your basement or crawlspace. Roof leaks are usually noticeable and should be repaired immediately. Rain coming through a wall may be less apparent, especially if it is a relatively small leak and the water remains inside the wall cavity. These kinds of leaks may occur around window or door frames, so it is important to replace any missing or cracked caulking. Rain seeping through the ground into your basement or crawl space may appear as damp, moldy walls or may be handled by a sump pump. In any event, you want to be sure that all rain coming from the roof, gutters, or across the landscape is directed well away from your house.

You also generate moisture when you cook, shower, water your indoor plants, use unvented space heaters, do laundry, even when you breathe. More than 99% of the water used to water plants enters the air. If you use an unvented natural gas, propane, or kerosene space heater, all the products of combustion, including water vapor, are exhausted directly into your living space. This water vapor can add up to 5 to 15 gallons of water per day to the air inside your home. If your clothes dryer is not vented to the outside, or if the outdoor vent is closed off or clogged, all that moisture will enter your living space. Just by breathing and perspiring, a typical family adds about 3 gallons of water per day to their indoor air.

Because air always contains some moisture, any air movement carries moisture with it. Did you know that your house breathes? We inhale and exhale through our noses, but your house inhales through one air pathway and exhales through another. Usually houses inhale around their bottom half and exhale around their top half. These air pathways include all available openings, both small and large. Back when homes had central fireplaces or open furnaces, the chimneys took care of most of the exhaling. Now, however, much of that job is handled by small leaks through your walls, floors, or ceilings. Remember that if any air is leaking through electrical outlets or around plumbing connections into your wall cavities, moisture is carried along the path.

The same holds true for air moving through any leaks between your home and the attic, crawl space, or garage. Even very small leaks in duct work can carry large amounts of moisture, because the airflow in your ducts is much greater than other airflows in your home. This is especially a problem if your ducts travel through a crawlspace or attic, so be sure to seal these ducts properly (and to keep them sealed!). Return ducts are even more likely to be leaky, because they often involve joints between drywall and ductwork that may be poorly sealed.

Moisture also moves through a process called diffusion. Diffusion occurs if some part of your home has a higher moisture level than another part, such as the movement of moisture from the bathroom to the bedroom after a hot shower has filled the bathroom with steam. Another example of diffusion is the movement of moisture through a floor above a damp crawl space and into the house above. Diffusion happens even if there is no air movement at all. Just as heat travels from a hot space to a cold space, even if it has to go through a wall, water vapor will travel from a space with a high moisture concentration to a space with a lower moisture concentration, again, even if it has to go through a wall. Cold air almost always contains less water than hot air, so diffusion usually carries moisture from a warm place to a cold place.

Liquid Movement can also happen within your walls, such as when water runs down an internal wall surface, or seeps through your insulation. Capillarity is another kind of liquid movement, and it can carry moisture from the ground up into your walls. This is the same process used by trees to carry water from their roots to their leaves. (Did you ever put a stalk of celery into a glass of colored water and watch the color climb to the leaves?). This process can carry water through concrete slab floors into your home. It can also carry water from the foundation into your walls, so your builder should include a vapor retarder between the foundation and the walls.

Moisture can also enter your home during the construction process. The building materials can get wet during construction due to rain, dew, or by lying on the damp ground. Concrete walls and foundations release water steadily as they continue to cure during the first year after a home is built. During the house’s first winter, this construction moisture may be released into the building at a rate of more than two gallons per day, and during the second winter at a slower rate of about one gallon per day.

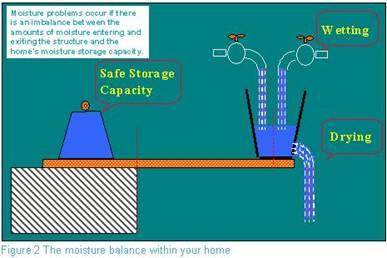

We have discussed how moisture moves through your house, but your house is also able to store moisture. All building materials, including the wood studs within your walls and the gypsum wallboard, can hold a certain amount of moisture and still do their job properly. So if your weather alternates wet times with dry times, the building materials may be able to hold the moisture until drier air carries it away, as illustrated in Figure 2. But if the drying times are not long enough, or often enough, the extra moisture will cause problems.

What Does Insulation Have to Do with Moisture Problems?

Adding insulation can either cause or cure a moisture problem. When you insulate a wall, you change the temperature inside the wall. That can mean that a surface inside the wall, such as the sheathing underneath your siding, will be much colder in the winter than it was before you insulated. This cold surface could become a place where water vapor traveling through the wall condenses and leads to trouble. The same thing can happen within your attic or under your house. On the other hand, the new temperature profile could prevent condensation and help keep your walls or attic drier than they would have been.

So how do you know what to do? Your home’s moisture performance will depend on the type and position of the insulation, whether you install a vapor retarder (these retarders are described later in this document), and where the vapor retarder is located. We used to think that the best insulation approach only depended on your weather. But now we know that it is more complicated than that. Moisture problems and their solutions depend not only on your climate, but on the type of house construction, the amount of moisture you produce inside the house, the way you ventilate your house, and the temperature conditions you maintain inside the house.

Why does the climate change the way you should use insulation? Remember that diffusion usually carries moisture from a warmer space to a colder space, and that moisture will condense to a liquid, or even solid, form if it contacts a cold surface. The location of the cold surface, and the location of the higher moisture concentration both vary with climate and season. If the outside air is colder than the inside of a home, then moisture from inside the warm house will try to diffuse through the walls and ceiling toward the cold, dry outside air. If the outside air is hot and humid, then moisture from outside will try to diffuse through the walls toward the dry, air-conditioned inside air. In both of these cases, what’s important is the difference between the inside and outside climates. So next-door neighbors could install the same insulation and vapor retarder but get very different results, depending on what temperatures they maintain inside their homes and how much moisture their lifestyles generate.

How does house construction impact moisture problems? Different materials will hold and transport moisture differently. For example, a brick surface will allow more moisture to pass than does aluminum siding, but the brick is also capable of storing moisture. And the house design will make a difference too. For example, attics, basements, and crawlspaces can be vented, or can be sealed and act as a part of your conditioned space. Insulation can be placed inside a wall, or on the inner or outer surface of the wall. These configurations obviously require different approaches if you want to avoid moisture problems.

So How Can You Avoid Moisture Problems?

Here are six things you should consider:

-

You need to prevent/stop all rain-water paths into your home by making sure your roof is in good condition and by caulking around all your windows and doors. If you are planning a new house, choose wider overhangs to keep the rain away from your walls and windows. You can also keep rainwater away from your basement walls or crawlspace by making sure that all water coming off your roof is directed away from your house and by sloping the soil around your house so that water flows away from your house. Be sure that dripping condensate from your air conditioner is properly drained away from your house. You can place thick plastic sheets on the floor of your crawlspace to keep any moisture in the ground from getting into the crawlspace air, and then into your house. These actions can also help reduce capillary water flows from the ground into your walls. You should also be careful that watering systems for your lawn or flower beds do not spray water on the side of your house or saturate the ground near the house.

You need to ventilate your home to remove the moisture that results from human activities within your home, such as breathing, bathing, cooking, etc. You especially need to vent your kitchen and bathrooms. You may be able to see mold (see a close-up view in Figure 3) that grows around your bathtub, but you will not be able to see mold growing inside the walls or in the attic. So, be sure that these vents go directly outside, and not to your attic, where the moisture can cause problems. Remember that a vent does not work unless you turn it on; so if you have a vent you are not using because it is too noisy, replace it with a quieter model. Some of the better vents are available with timers or moisture sensors so that you can be sure that the vents run long enough to remove all the excess moisture from that room. (While you are in the bathroom, it is also a good idea to check the caulking around your tub or shower to make sure that water is not leaking into your walls or floors when you bathe.)

When you think about venting to remove moisture, you should also think about where the replacement air will come from, and how it will get into your house. Many older homes have relied on leaky construction, drawing in their fresh air around window and door frames, building corners, wall-foundation joints, wall-roof joints, chimneys, etc. Air coming into your home through these pathways often travels through places you cannot see, such as wall cavities, the space between floors, the crawlspace, or attic. If this outside air contains moisture, you will effectively be pumping moisture into these unseen places. As we seal up our homes to save energy, we need to replace these uncontrolled air pathways with energy-efficient pathways. Air-to-air heat exchangers can keep the indoor air at a healthy moisture level without increasing your energy costs. In humid regions, attic ventilation may also be a moisture source because you may be pulling air into your attic that has more moisture in it than the air in your home.

It is important to seal up all air-leakage paths between your living spaces and other parts of your building structure. Measurements have shown that air leaking into walls and attics carries significant amounts of moisture.

Plan a moisture escape path. Some moisture will always be present in your home. You can help this moisture escape with well-planned ventilation or by careful selection of your building materials. Typical attic ventilation arrangements are one example of a planned escape path for moisture that has traveled from your home’s interior into the attic space. You can also use a dehumidifier to reduce moisture levels in your home, but it will increase your energy use and you must be sure to keep it clean to avoid mold growth. If you use a humidifier for comfort during the winter months, be sure that there are no closed-off rooms where the humidity level is too high.

You can use vapor retarders to reduce moisture diffusion through your walls, floors, and ceilings. This is relatively easy to do when building a new house, but there are a few things that you can do for existing houses as well. The kind of vapor retarder you should use, and where you put it, depends on whether moisture is more likely to be moving into or out of your house. If moisture moves both ways for significant parts of the year, you may want to avoid the use of a vapor retarder completely.

What is a Vapor Retarder?

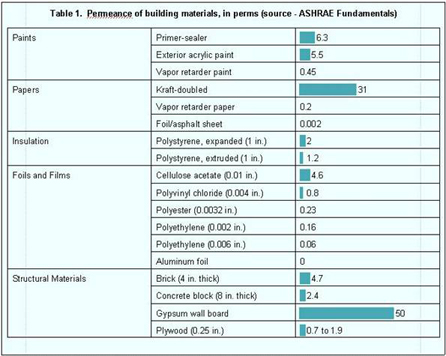

Vapor retarders are special materials including treated papers, paints, plastic sheets, and metallic foils that reduce the passage of water vapor. Tests are made to measure how much water vapor can travel through each material, and the results are called permeance, or perms. The lower the perm, the better the vapor retarder. Table 1 lets you compare the permeance of some of the vapor retarders used in buildings.

Where Can I Learn More?

If you want to learn more about controlling moisture in your home, there are several useful books available:

Moisture Control in Buildings, Heinz R. Trechsel, Ed., American Society for Testing and Materials, Philadelphia, PA, 1994, ISBN 0-8031-2051-6, www.astm.org

ASHRAE Handbook of Fundamentals, American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc., Atlanta, GA, 2001, www.ashrae.org

Moisture Control Handbook, by Joseph W. Lstiburek and John Carmody, Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, NY, 1993, ISBN 0-442-01432-5, (earlier edition available as ORNL/Sub/89-SD350/1 from the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA, 1991), www.ntis.gov

Environmental Protection Agency web site about molds and moisture:

www.epa.gov/iaq/molds/moldguide.html